2021.

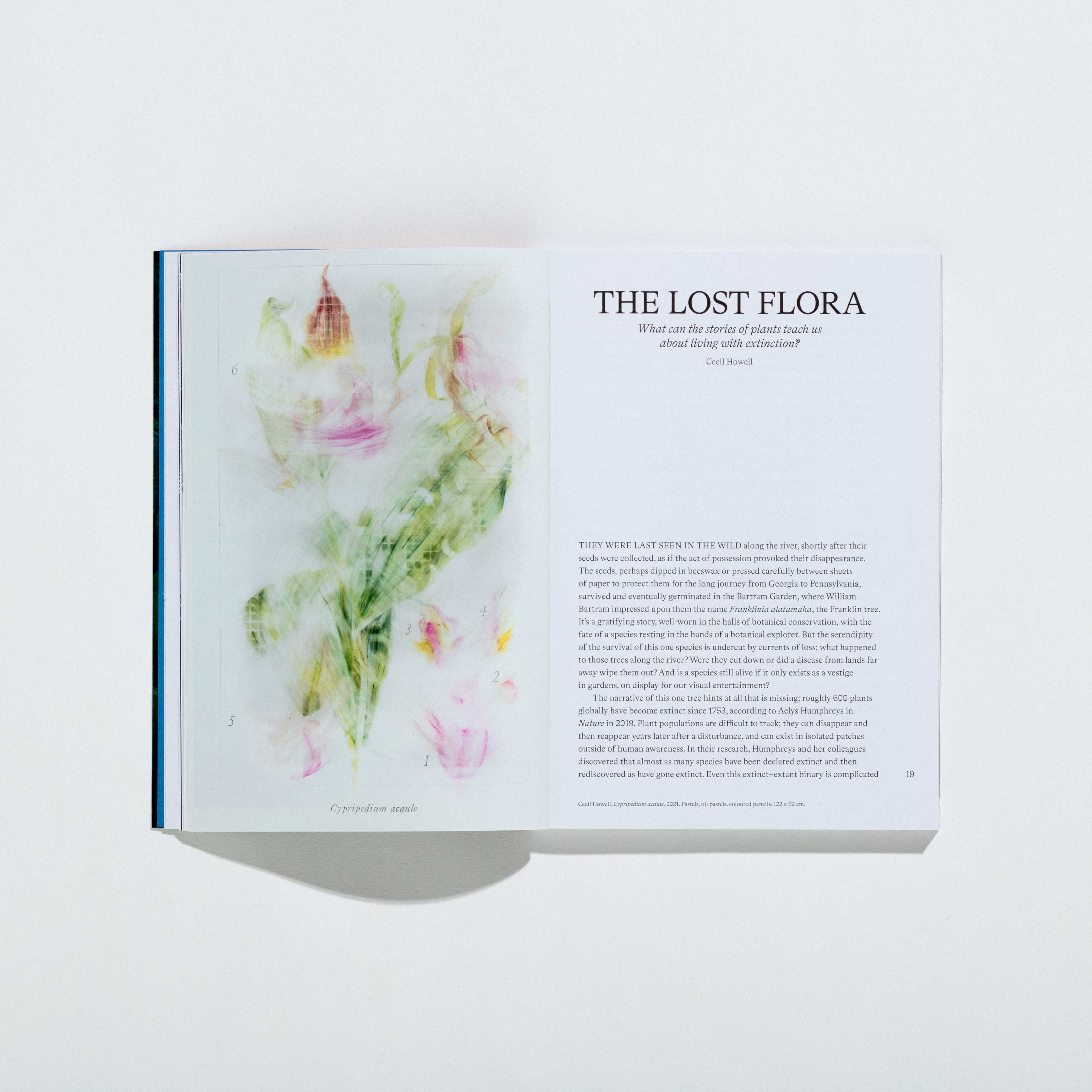

The Lost Flora

![]()

![]()

Arundinaria gigantea | Clay, Graphite, and Pastel | 22” x 30”

Castanea dentata | Watercolor, Graphite, and Guache | 22” x 30”

The following is an excerpt from a publication in Wonderground Magazine that explores the North American plant species that became endangered or extinct since colonization. The magazine can be found here.

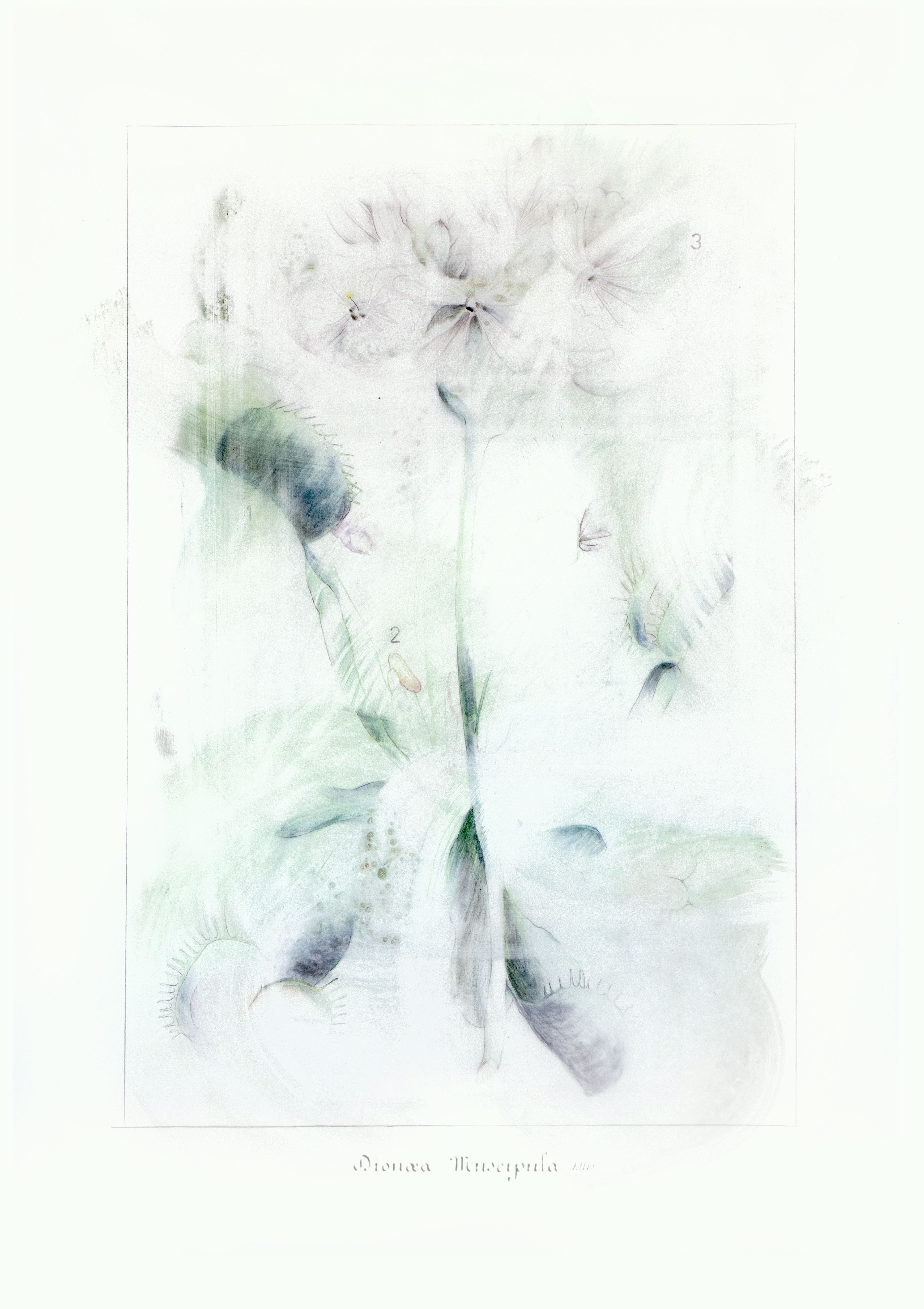

They were last seen in the wild along the river, shortly after their seeds were collected, as if the act of possession provoked their disappearance. The seeds, perhaps dipped in beeswax or pressed carefully between sheets of paper to protect them for the long journey from Georgia to Pennsylvania, survived and eventually germinated in the Bartram Garden, where William Bartram impressed upon them the name Franklinia alatamaha, the Franklin Tree. It’s a gratifying story, well-worn in the halls of botanical conservation, with the fate of a species resting in the hands of a botanical explorer. But the serendipity of the survival of this one species is undercut by currents of loss; what happened to those trees along the river? Were they cut down or did a disease from lands far away wipe them out? And is a species still alive if it only exists as a vestige in gardens, on display for our visual entertainment? The narrative of this one tree hints at all that is missing; roughly 600 plants globally have become extinct since 1753 according to Aelys Humphreys in a 2019 article published in Nature. Plant populations are especially difficult to track; they can disappear and then reappear years later after a disturbance and can easily exist in isolated patches outside of human awareness. In their research, Humphreys and her colleagues discovered that almost as many species have been declared extinct and then rediscovered as have gone extinct. Even this extinct-extant binary is complicated with plants which, unlike many animals, can also be preserved and propagated, in labs and botanical gardens, even if they have ceased to have a viable wild population -- a state known as ‘functional extinction’. More and more plants are headed towards this purgatory, as we continue to invest in collecting and storing the seeds of species, while simultaneously diminishing the capacity for these same plants to survive in situ. This is the case for the Franklin tree, which is now relatively widespread, but in such isolated instances that its existence hardly registers. We haven’t lost the species, but rather the potential of a population.