Journal

To Fix a Cloud

Summer 2022

Contained in the depths of our finest institutions are vast collections of the more than human world. Categorized and cataloged, these materials inform much of the way we understand the world around us. There is a paradox inherent in collecting; the quest to pin something down and define it as an individual can obscure the very entanglements which all life depends on.

This installation is a cumulus of cloud like forms, made from paper and wax, pinned to the earth with wooden dowels. The sculpture is at once a riff on the desire to collect, but also a luminous form, which changes with the light and reflects nearby colors. It invites viewers to walk under it, observing the way light filters through the paper, and observe it as a form from afar.

Made out of paper, wax, and wood, this sculpture is designed to be a temporary installation, easily disassembled and returned to the earth.

Plant Anatomy of the Endangered, Extinct, and Non-Existant

Spring 2022

This winter I returned to the Oak Spring Garden Foundation to continue my exploration of endangered plants, as a means of examining the scientific lens, celebrating the abundance of plant morphologies, and memorializing species now extinct. Using paper casting techniques, I created plant anatomy models, inspired by the 19th century Brendel models used for botanical education. Rather than creating archetypal models, the forms I make are inspired by endangered, extinct, and non-existent plants. They are part sculpture, part diagram, part fiction, and part fact.

Unkown Phallaceae sp.

Adenophorus periens

Adenophorus periens Erioderma pedicellatum

Erioderma pedicellatum

Possibly Mnium hornum

Seed pod of Asclepias meadii

The Lost Flora

Fall 2021

In the summer of 2021 I had the opportunity to spend three weeks in the archives and landscape of the Oak Spring Garden Foundation in Upperville Virigina. The archives contain a vast collection of early botanical catalogues from colonizers of North America. While these early catalogues are by no means comprehensive, I was curious to examine them in the context of loss: What can the plants in these pages teach us about how we react to, preempt, and contextualise extinction? How did this era shape our knowledge of flora and what was lost in translation with the advent of a global categorization system? The following images and text are an excerpt from a piece published in Wonderground, a biannual journal published by Plant Hunter.

The visual pieces I created are based on illustrations found in plant catalogues from the 18th and 19th century. After drawing the plants, I removed the pigment using sponges, sandpaper, bleach, glass cleaner and erasers. There was an intimacy in using household cleaning supplies to wipe away the drawings; it centredre some of the abstract ideas around loss onto my body and the daily gestures we use to clean and control our spaces. The process of erasure also created new forms, forms that lack the “thingness” that the original illustrations were trying to capture, but perhaps shed light on other truths about the plants: their interconnectedness, their temporality, or the way they may be perceived by other species. To paraphrase Terry Tempest Williams, in undoing there is also becoming.

Many thanks to the Oak Spring Garden Foundation for their generosity in sharing the archives and providing both the space and time to create this work and the North American Cultural Laboratory for providing a quiet space to write.

“They were last seen in the wild along the river, shortly after their seeds were collected, as if the act of possession provoked their disappearance. The seeds, perhaps dipped in beeswax or pressed carefully between sheets of paper to protect them for the long journey from Georgia to Pennsylvania, survived and eventually germinated in the Bartram Garden, where William Bartram impressed upon them the name Franklinia alatamaha, the Franklin Tree. It’s a gratifying story, well-worn in the halls of botanical conservation, with the fate of a species resting in the hands of a botanical explorer. But the serendipity of the survival of this one species is undercut by currents of loss; what happened to those trees along the river? Were they cut down or did a disease from lands far away wipe them out? And is a species still alive if it only exists as a vestige in gardens, on display for our visual entertainment? The narrative of this one tree hints at all that is missing; roughly 600 plants globally have become extinct since 1753 according to Aelys Humphreys in a 2019 article published in Nature. Plant populations are especially difficult to track; they can disappear and then reappear years later after a disturbance and can easily exist in isolated patches outside of human awareness. In their research, Humphreys and her colleagues discovered that almost as many species have been declared extinct and then rediscovered as have gone extinct. Even this extinct-extant binary is complicated with plants which, unlike many animals, can also be preserved and propagated, in labs and botanical gardens, even if they have ceased to have a viable wild population -- a state known as ‘functional extinction’. More and more plants are headed towards this purgatory, as we continue to invest in collecting and storing the seeds of species, while simultaneously diminishing the capacity for these same plants to survive in situ. This is the case for the Franklin tree, which is now relatively widespread, but in such isolated instances that its existence hardly registers. We haven’t lost the species, but rather the potential of a population.”

Thinking like a salt dome

Spring 2021

“When we depersonalize the river, the mountain, when we strip them of their meaning — an attribute we hold to be the preserve of the human being — we relegate these places to the level of mere resources for industry and extractivism.”

— Ailton Krenak

Mapping salt domes is not just an exercise in tracing forms, but rather in becoming intimate with another force. One that operates across millennia, without sunlight, without air; a substance so thoroughly opposite of our human cells. Yet we are entangled with it’s existence. The force of salt moving between geological strata, creates oil deposits which become our fuel, and consequently our ability to travel the world, enabling us to collapse 26,000 miles into mere hours in a plane. But as we hurtle forward, faster than ever before, we depend more upon the movements of deep time. Movements that, when measured in the span of a human life, are invisible and therefor rendered static by mapping.Facing the Planetary

Fall 2020

I am deeply struck by this most beautiful call to thinking by William Connolly.

“What follows is a series of attempts to face the planetary. Not only to face down denialism about climate change but also to define and counter the “passive nihilism” that readily falls into place after people reject denialism. By passive nihilism I mean, roughly, formal acceptance of the fact of rapid climate change accompanied by a residual, nagging sense that the world ought not to be organized so that capitalism is a destructive geologic force. The “ought not to be” represents the lingering effect of theological and secular doctrines against the idea of culture shaping nature in such a massive way. These doctrines may have been expunged on the refined registers of thought, but their remainders persist in ways that make a difference. Passive nihilism folds into other encumbrances already in place when people are laden with pressures to make ends meet, pay a mortgage, send kids to school, pay off debts, struggle with racism and gender inequality, and take care of elderly relatives. Or, similarly, the may eke out a living in the forest and try to figure how to respond when a logging company rumbles into it. Or, on another register, they may teach students who both want to believe in the future they are preparing to enter and worry whether that lure has itself become a fantasy. The sources of passive nihilism are multiple. Under its sway, as we shall see, many refute climate denialism but slide away from stronger action. That is the contemporary dilemma. Few of us surmount it completely. But perhaps it is both necessary and possible to negotiate its balances better. ”

— William E. Connolly, Facing the Planetary

Water as Cake

Summer 2020

Some of my meanderings (both written and visual) on the waterwars in the American South were recently published in Burnaway Magazine. A tiny excerpt is below; for the full article, visit this link.

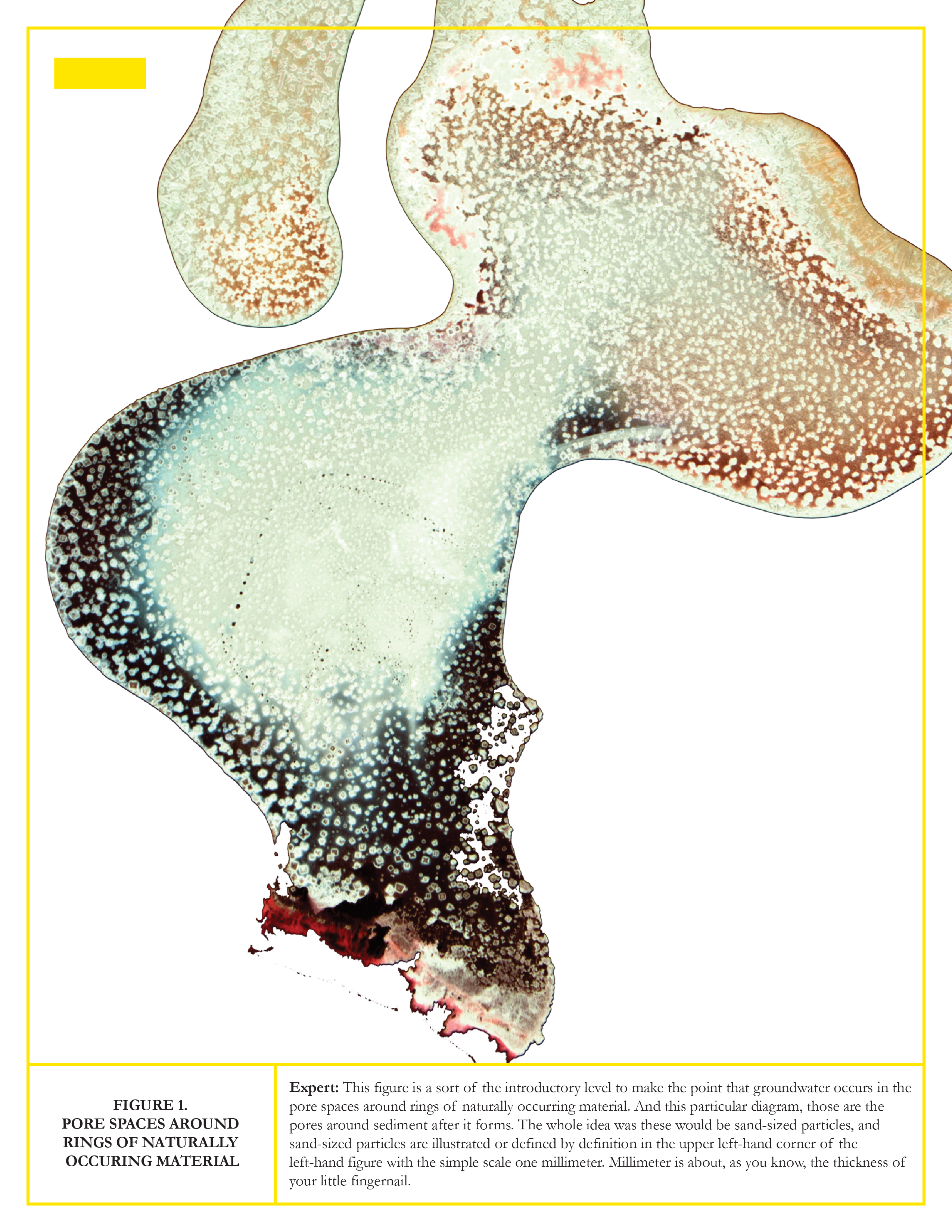

On February 25, 2020, the Honorable Eugene E. Siler heard the closing arguments from the states of Tennessee and Mississippi regarding a dispute over who owns the groundwater in the Middle Claiborne Aquifer, one layer in the larger Mississippi Embayment Aquifer system, a mushy layer cake of rocks and water that spreads underneath seven states. Judge Siler will send his recommendations on the ruling to the Supreme Court, making this the first groundwater case ever ruled on by our nation’s highest court. While surface water use disputes are common, particularly in the arid west, this case is conceptually striking as it begs us to imagine ancient waters flowing below our terra firma, beneath our farms and cities, fashioning us as flotsam on this slushy substrate. While the cartographic boundaries of our states are often revealed as absurd by the landscape (think orthogonal lines slicing up a watershed into a jigsaw of bureaucracy), the invisibility of the aquifer upends our understandings of state sovereignty and commodification as its waters slowly move below state lines, evading easy classification and possession.

Monoprint of bedroom shadow

A Reorienting

Spring 2020

It is a feeling familiar to those who travel frequently or maybe imbibe too much: I wake up, my eyes still closed, wondering where I will find myself when I open my eyes. The irony of this is that I’ve woken up in the same bed, in the same room, for over a month now. But without seeing my surroundings, I am at a loss. The sounds and smells that would normally fill in the neurological gaps left by my closed eyes are unintelligible. A vague memory alights upon my mind: waking up in tropical city, sometime in my teens, lying in bed listening to the bird chatter, a morning commute in a different language, smelling the diesel fuel. I didn’t know that memory was there. Is it the intensity of bird song that makes it reappear? That makes me think for the briefest moment that that is where I will wake up? Why am I not thinking of the home in the country that I grew up in? The bird chatter marked the mornings there, but it doesn’t feel quite right. Despite the lack of cars, horns, and voices, there is still some urban imprint on the smells and sounds that makes me realize I am in a city.

It is the strange feeling of being disoriented, while also knowing exactly where you are. The city we live in is intact, the buildings are standing, the season moves forward. Without altering one brick, this pandemic has shifted the substance of this city. I have always loved the imbrication of memory and place, the moment when your mind connects the place where you are to some figment of memory and all of a sudden you are on a ferry in Lake Superior remembering the monkeys on the side of the highway in Mumbai. Smells usually trigger this most easily, although sometimes a rare emotional quality can be a divining rod to a long forgotten memory. Simon Schama writes about this most beautifully in his book Landscape and Memory, which I have found a resource for thought and meaning during this time.

“For it seems to me that neither the frontiers between the wild and the cultivated, nor those that lie between the past and the present, are so easily fixed. Whether we scramble the slopes or ramble the woods, our Western sensibilities carry a bulging backpack of myth and recollection. ”

— Simon Schama

Unintended Consequences

Spring 2020

On Sunday, The NY Times carried a piece on declining nitrogen dioxide levels in cities as fewer people use their cars. This is one of the many consequences of the Corona virus pandemic. The human toll, in deaths, psychological impact, and economic loss, will, undoubtedly, be immense. On the other hand, there is the drastic reduction in pollution, as our economy comes to a red light. I am not speaking of silver linings, I don’t believe that the gains we will experience in air quality do anything to balance the loss of life. What I am curious about, to paraphrase Albert Camus, is the way that we will construct meaning out of this microbe. For instance, there will no doubt be calls to de-globalize, blaming the rapidity of the spread on our interconnected community. Others will want to reinstate business as usual, blaming the pandemic entirely on the wet markets of China. The narrative I find myself drawn to is the illusion of stability that we operated under, and perhaps will return to, pre-virus. This idea of stability, that markets will continue to grow, that investments will keep returning profits, is essential to our narrative, and yet, even before this virus, we are witnessing a rapidly changing climate and steep rise in extinction of non-human species. Acknowledging that the science of change and loss are true also means that we need to operate differently, but that goes against our instinctual desire for stability. Can the vast disruption caused by a 0.125 micrometer virus help us recast our narrative? Isn’t there something to be learned in our fragility?

This is where I am finding meaning in this moment.

The Biography of a River

Spring 2020

This series, which captures a 3 mile section of the Flathead River from 1945 until 2015 (based on data collected by the Flathead Biological Research Station) explores the undulations of an untrammeled floodplain. Inspired by Iris Murdoch’s thoughts on beauty (see below) as a relationship between time and object, this series pairs the path of the river with monoprints of snow melting, the same process which feeds the Flathead River.

These prints were created at the MacDowell colony. The river forms are embossed from models of the river and the monoprints were created by inking snow and allowing it to melt on the monoprint plate.

Meanderings on Beauty

Fall 2019I recently returned from a residency at The Flathead Bio Station, an excellent research facility dedicated to the monitoring and understanding of Flathead Lake in Montana. Over the last century they have used the lake as their muse, expanding our understanding of limnology and capturing the workings of one of the most intact watersheds. One of their long-term monitoring sites is along the middle fork of the Flathead River, which runs along the mountainous border of Glacier National Park, before spilling into a wide flood plain. Untrammeled by levees or culverts, the water is free to undulate, creating a valuable matrix of habitat with each move. On the ground, a floodplain landscape can be chaotic and confusing, with pockets of dense scrubby vegetation, stretches of barren river rocks, and eddies of debris. There are no scenic vistas and it is hard to take a photograph that captures the life and beauty of the space. The Everglades was the first national park to be created in order to protect a vital ecosystem, otherwise we often rely on grand vistas or distinct landforms to guide our conservation efforts. But this approach obviously has its limits: it ignores landscapes, often vital ones, that don’t appeal to our cursory glance, and is, at its core, human-centric. If we are to find beauty in the more complicated landscapes, perhaps we need to both define beauty differently as well as see landscapes differently. Personally, I subscribe to Iris Murdoch’s definition:

Beauty is the convenient and traditional name of something which art and nature share, and which gives a fairly clear sense to the idea of quality of experience and change of consciousness. I am looking out of my window in an anxious and resentful state of mind, oblivious of my surroundings, brooding perhaps on some damage done to my prestige. Then suddenly I observe a hovering kestrel. In a moment everything is altered. The brooding self with its hurt vanity has disappeared. There is nothing now but kestrel. And when I return to thinking of the other matter it seems less important. And of course this is something which we may also do deliberately: give attention to nature in order to clear our minds of selfish care.

- Iris Murdoch (via Brainpickings)

By this definition, beauty is not a state of being, but rather a relationship between two objects. It is also subject to timing, revealing itself with the flap of a wing and the shift of an eye. I visited the Everglades years ago, canoe camping along the mangrove shores. The sun was glaring, the water brown, the leaves sun-burnt green. It was only in the prolonged witnessing of the landscape that the beauty emerged, the sound of a snake falling into the water, a shark fin emerging from the brown depth, epiphytes tucked into the branches of the trees. Maybe, like the slow food movement, we need a slow beauty movement . A movement encouraging us to see more and look less, a counterpoint to the commodification of landscapes on social media.

Terra incognita

Fall 2019

“...consider a dialogue. In such a dialogue, when one person says something, the other person does not in general respond with exactly the same meaning as that seen by the first person. Rather, the meanings are only similar and not identical. THus, when the second person replies, the first person sees a difference between what he meant to say and what the other person understood. On considering this difference, he may then be able to see something new, which is relevant both to his own views and to those of the other person. And so it can go back and forth, with the continual emergence of a new content that is common to both participants...[they are] creating something new together. ”

— David Bohm

In David Quamann’s delicious book, The Tangled Tree, he expertly unravels the story of horizontal gene transfer, our rather our current understanding of it. The ability of genetic code to migrate between species, even between kingdoms, throws our understanding of evolution. It also calls into question our understanding of the individual, at the level of organisms to that of species. Our bodies, made of 10% human cells and 90% of bacteria, viruses, etc., are colonies as much as our towns are. To reference David Bohm, our cells are in a constant dialogue with each other, creating something far different than their original genetic makeup would predict. We have mapped our genetic code and most of the world, seen it with our eyes, our microscopes, or our satellites, and yet, there is still so much we don’t know, still so much terra incognita. It seems that while we have amassed the technology to see a cell, a body, a forest, or a mountain range, we haven’t yet figured out how to see the dialogue between - this is our terra incognita.

Lost at Sea

Fall 2019

At the north-western edge of our continent lies the Tongass National Forest: a wilderness of stunning beauty and solitude, filled with ancient trees, whales breaching, and the sound of sea otters cracking shells. It is also filled with our trash. The U.S. Forest Service invited me to accompany them on one of their wilderness monitoring programs to the West Chichagof–Yakobi Wilderness; a ten-day kayaking trip along the outermost islands in the forest. While the purpose of the trip was to monitor human activity, it became clear that human waste is far more pervasive than humans themselves. Over the course of the trip, we picked up 580lbs of trash, including 600 plastic bottles.

At the murky edge of humans are the objects we create, the objects we buy, the objects we eventually toss. Here, in the West Chichagof–Yakobi Wilderness, our objects are entangled in the environment; buried under a thick moss, caught on a driftwood branch, entwined in seaweed. They are ghosts of massive storms, fishing expeditions, and above all human hubris.

In a Forest

Summer 2019

Lake Superior was once a lava bed. Or rather, it still is a lava bed, it’s just a billion years old and now covered in some of the deepest, clearest water in the world. Through forces like uplift, compression, and collapse, the lava bed curled up at the edges and created a peninsula on one side and an archipelago on the other (similar to lying on a slightly deflated air mattress — when compressed in the middle the mattress edges will rise up). Fast forward through deep time to our present day, where the archipelago once scraped and depressed by the mass of glaciers, is now on the rebound, rising roughly one foot per century — that the land can still be feeling the release from a weight lifted 10,000 years ago is profoundly beautiful.

Earlier this month I returned from 20 days on the Archipelago, called Isle Royale National Park. I was visiting the park as an artist-in-residence, researching the complex entanglement of humans/non-humans, biotic/abiotic elements, and how these play out over time. My project was to create an atlas for the park: a series of maps that explore these stories, but beyond that I was free to draw/walk/read as I pleased. I grew up wandering the deciduous woods of New England and a walk in a forest gives me the feeling of finding a phantom limb. It’s a feeling that I don’t realize is missing in my everyday life, but once I recognize it, it seems essential to being. There is much talk and research these days recognizing the importance of our relationship with the natural world, including forest Bathing, doctor’s prescribing the outdoors, and our chemical reaction to being in a forest; all of which deeply interest me. We (oxygen consumers) are involved in a grand symbiotic relationship with plants, which in turn are involved in a grand symbiotic relationship with fungi, and on and on. But breaking the relationship into parts undermines the expansive quality of a forest. Perhaps Herman Hesse said it best:

For me, trees have always been the most penetrating preachers…They are wiser than we are, as long as we do not listen to them. But when we have learned how to listen to trees, then the brevity and the quickness and the childlike hastiness of our thoughts achieve an incomparable joy. Whoever has learned how to listen to trees no longer wants to be a tree. He wants to be nothing except what he is. That is home. That is happiness.

The prodigal son

Summer 2019

Niagara Falls played an inspiring roll in the creation of the National Parks. Not so much because of it’s own inspiring scenery, but rather as a warning to the unorganized development that arises around places of awe-inspiring beauty. Developers/shop owners/tourists etc. capitalize on the scenery, creating a crust of development anywhere there is a prospect. One could call this awe-mining, although expanding the definition of “prospecting” seems appropriate too. Anna Tsing refers to the process by which “living things made within ecological processes” become capitalist commodities as “salvage accumulation.” As she so smartly points out this is not “an ornament on ordinary capitalist processes; it is a feature of how capitalism works.” Whether we call it awe-mining, prospecting, or put it under the umbrella of salvage accumulation, this phenom happens all over the place, usually only abated by geographical limitations. For Isle Royale National Park, the remote volcanic archipelago in Lake Superior, the lesson was learned on Mackinac Island, where resorts and fudge shops replaced forest and field. We often speak of the power of failure in terms of business: companies that can support failure are able to grow and adapt. But landscapes, too, can become collective lessons on the need for bigger vision and the communal benefit of sharing a place of striking awe. The science of awe points to the benefits of these experiences for humans, including increased connectedness with other people. Everyone who I spoke with on Isle Royale, save one grumpy grandmother, described this feeling in one way or another. Our desire to understand this feeling, to research it and support it with data, is perhaps a sign of our growing interest in advocating for the more natural spaces, spaces less overtly contaminated by human economies. That mistakes are part of the process of conservation, perhaps even essential, points to the messiness and unpredictability of life. Isle Royale exists as a park because another place doesn’t - the two places converge, even as their fates diverge further.

Unlasting Impact

Summer 2019

“We need to make a shift in our imagination about cities. … We need to use our resources more efficiently to extend the expiry date of our planet. We need to change urban design cultures to think of the temporal, the reversible, the disassemblable.”

— Rahul Mehrotra

How will we be remembered if nothing is left behind? This question may seem irrelevant given the depth of the Athropocene’s impact. As Jan Zalasiewicz noted in a recent segment on ‘On the Media’ - our vast geological thumbprint will include an enormous amount of chicken bones (expertly preserved in our landfills) and the fossilized silhouette of millions of soda cans (the aluminum will eventually dissolve, leaving behind a 335mL void). In researching Isle Royale, I’ve come across a gap in the common historical narrative that speaks to the absence of material history. Roughly 6,000 years ago, miners actively tapped the copper reserves on Isle Royale, as evidenced by the ancient pit mines, tool markings, as well as the lead pollution David Pompeani found in nearby sediment cores. The mining stopped suddenly, only to be resumed in the 1840s when rising copper demand and the discovery of Copper Country led to a boom. In between these two events, there is very little evidence of anyone living on Isle Royale and numerous accounts report that no one did. Timothy Cochrane disputes these reports in his book, Minong: The Good Place, where he evidences with great detail the oral record of Ojibwe families living on Isle Royale during the summer months. But since the Ojibwe were nomadic and left little physical record of their daily living, their story has been left out. Now perhaps the physical record that they did leave is imperceptible to us now — but in fact does exist — we just don’t know what to look for or what to compare it against, like the color-blind being asked to compare red and green. Or perhaps their record was actually fleeting, they lived on the island, but in such a way as to not leave a trail of lead poison or the markings of a building footprint. Consider how different this is compared to your own footprint in three months, how many clamshells or tons of carbon dioxide are left in a human’s wake? I love the things we can make, but it seems like so much of what we actually leave behind are not the intentional fruits of creative labor, but the unintentional byproducts (I believe that these are one and the same). And yet, as the Ojibwe of Isle Royale show, it is also possible to live so lightly in a place that the impact is imperceptible. I don’t think this needs to be the goal, but I do believe that approaching consumption and creativity with an eye towards the archeological record may speak to the human mind.

The half-life of a cotton t-shirt

Summer 2019

A female Northern Pike fish can live into her thirties. That’s thirty years of swimming around the cold, oligotrophic, waters of Lake Superior eating smaller fish (and sometimes her own spawn). As she eats, her body fat slowly accumulates environmental toxins, like Mercury, PCBs, and PAHs. A lipid analysis reveals patterns in human consumption, chemical creativity, and global circulation.

When DDT was banned by the EPA, Toxaphene filled the role of the most abundantly used pesticide. An amalgamation of over 670 chemicals, Toxaphene indiscriminately kills insects, causes cancer, and mutates genes. While Toxaphene was predominantly used in the Southeast on cotton crops and was banned in 1990, Lake Superior is highly saturated with the chemical. Winds from the southeast brought the chemical north, where it reacted with the cold expansive surface water and stayed there, embedding itself into the food web.

It’s hard to imagine that buying a cotton tee in 1982 would have affected the Lake Superior ecosystem in 2019. Every decision we make will cascade out in ways beyond our current imagination, beyond the limits of our current knowledge. What is the half-life of a decision?

A new vision for the new Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade: Endangered species balloons, like the Limosa Harlequin frog

(Atelopus limosus) floating through New York City’s streets.

(Atelopus limosus) floating through New York City’s streets.

The Thick Now

Spring 2019

In Suzannah Lessard’s exquisite new book, The Absent Hand, she reflects upon our cultural narratives that give meaning to place and explain the landscapes we choose to protect. Our country’s romantic love of wilderness, for example, led to the formation of the National Parks. But as Lessard points out, Yosemite, the archetype of wilderness and beauty, was long populated by Native Americans before it became a park. Any obvious signs of human activity were removed from the valley when it became a National Park, in order to preserve it as a diorama of untouched wilderness. Lessard articulates that while romance was previously a tool for conservation, it willfully ignored our history of racism, violence, and environmental destruction. “What we really need from landscape now is truth.” She goes on to say:

“Where our romantic deflection of the truth may have served some good purpose once — the glory of the romantic view of nature infused with transcendence, for example — it now seems to stupefy more than awaken.”

And awaken, we must. The UN report released earlier this week forecasts the troubling century we have in front of us, unless we reckon with ourselves. I’ll admit, I feel dismal. But as Dylan Thomas says:

“Do not go gentle into that good night”

From left to write: Selk’nam in ritual dress (photograph by Martín Gusinde) | Yayoi Kusuma | Wilder Mann series by Charles Fréger | May the Horse Live in Me by Marion Laval-Jeantet and Benoit Mangin

From left to write: Selk’nam in ritual dress (photograph by Martín Gusinde) | Yayoi Kusuma | Wilder Mann series by Charles Fréger | May the Horse Live in Me by Marion Laval-Jeantet and Benoit Mangin

In Dissolving the Human

Spring 2019

In thinking through the relationship between the human-nonhuman, I am drawn to images that dissolve the human form. Something expansive happens when the body becomes pattern, animal, or distorted enough that it is neither. So much of art and religion is about the human condition. To some extent the work above is no exception, but each piece feels as though it is tracing the edges of humanity: the border between human-spirit, human-pattern, human-animal. As if scuba divers in the deep ocean, these photographs are explorations of the remote corners of humanity.

An Acre

Spring 2019

A Man and a Youth Ploughing with Oxen by Nicolaes Pietersz Berchem. Part of the National Gallery, London collection.

An acre: historically defined as the area of land a pair of oxen could plow in a day. A measurement of space and time. A measurement of technology. A measurement of non-human strength. A measurement of cultivation.

This summer I’ve been selected for three artist residencies, during which (or rather afterwards) I will produce a series of cartographic diagrams that explore place through space, time, and experience. The residencies will begin in Isle Royale, the national park in at the northernmost corner of Michigan, followed by a residency with the US Forest Service in the Alexander Archipelago off of southeast Alaska, followed by three weeks at the Flathead Lake Bio Station with Montana Open AIR.

One thought I’ve had for organizing the work is to create an Atlas of Measurement: using the constructs of different measuring units to bring together seemingly disparate topics. For instance a fathom in regards to Isle Royale had multiple meanings. For ships navigating the reefs around Isle Royale, the fathom as a unit of water depth became the lens through which sailors experienced the island. For copper miners excavating mine shafts on the island, the fathom became a unit of payment ($20/fathom), as they dug deep into the earth looking for copper veins. While this is a decidedly human lens, can it be co-opted to tell the non-human story as well?

On Communicating with Non-Humans

Spring 2019

The collage above brings together fragments of thought from Timothy Morton’s brilliant essay, X-Ray in the collection, Prismatic Ecology. Of particular interest to me, are his thoughts on science and the power we give it over non-humans. He posits the following:

“Things are caught in a circle: they are real because they are measured, because measuring measures them. And the humanities therbey ceded a giant area - the area of non-human beings - to science, happy to occupy its ever-shrinking island on the ocean of reason, constantly about to be inundated by the global warming of science and technology, with it ever-encroaching waves of nihilism”

Put simply we have limited ourselves to the human realm, letting only certain specialists be our interpreters of the non-human. But as Morton states, “at the very same time as Western humans are arguing that we have no direct access to the world, we are intervening in it more directly than ever before”. Our waste, our cities, even our conservation efforts are forms of communication with non-humans. In this way, every person is in contact with the non-human.

The above image is of a California Condor, the xray reveals human trash lodged in the condor carcass. While obviously a tragic image, perhaps Morton’s understanding will move our discourse beyond the empty feelings of sadness (followed quickly by buying a kombucha and cliff bar) towards an understanding of the agency of both the individual human and non-human. In this discourse how do we want to communicate? How can we listen?

More from Timothy Morton.

On Defining Landscapes

Spring 2019

“Landscape almost always appears as a complex imbrication of immediate reality and remembered elements.”

— Antoine Picon

The above quote from Anton Picon inspired me. If mapping is how we conceptualize large landscapes, how do we use it to describe the abstract and physical territories that landscapes occupy? Picon goes on to say:

“But the non-linearity of the interaction between what happens beneath the eye and what is recreated by the mind, using culture as a reservoir of visual and emotional references, has seldom been acknowledged. Hence the recurring confusion between memory and history plagues many reflections on the question. Although many of the features of digital culture seem to be adverse to memorial aspects, beginning with the impression that it bathes in the everlasting present of online sociability, digital culture can actually throw a new light on how memory interacts with the other dimensions that shape landscape. The presentist attitude generated by real-time encounters cannot indefinitely postpone the realization that our world cannot be reduced to the thin layer of stimuli and responses that belong to the immediate present.”

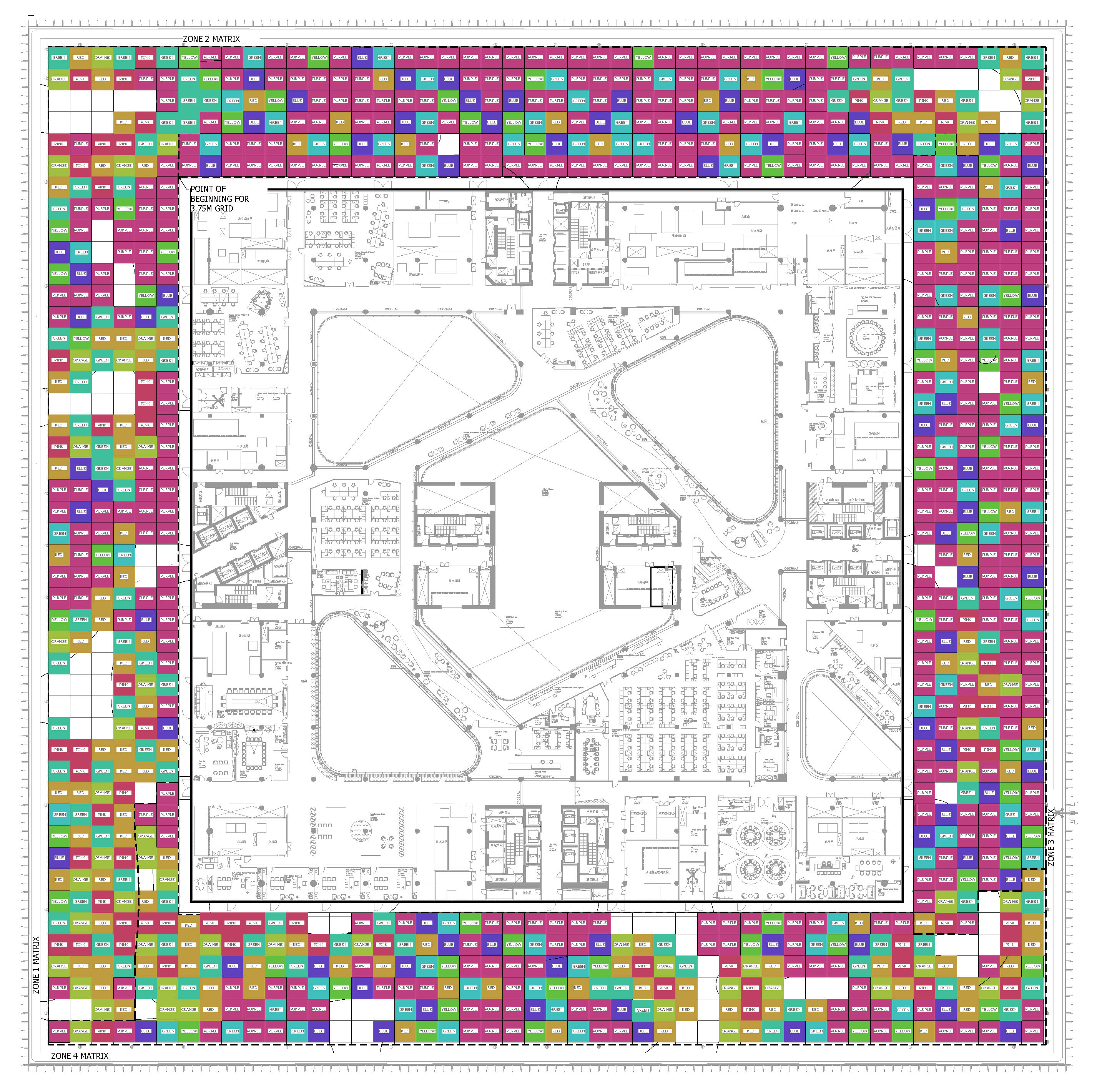

On Modular Planting

Fall 2018

How can we create complex plantings in construction documents?

The 4-acre roof of the Tencent Campus was an exciting challenge to take on. We wanted the planting to feel continuous and wild, but we also wanted to create a color scheme where the flower color subtly shifts from hot reds and pinks in the southeast corner, to soothing blues and whites in the northeast corner. Inspired by Thomas Rainer’s blog post and the beautiful modular planting by Dan Pearson at Millennium Forest, we designed a modular planting system. Each color represents a different plant layout. The contractor grids out the site, marks the color of each grid unit, and then lays down a corresponding stencil to spray paint the locations of each plant. The planting plan provides the details of which plant goes in each location, but the question of spacing and density is answered by the stencils, allowing the contractor to work efficiently and our role on site to be limited to making adjustments, rather than laying out each plant.