Cecil Howell —

Art, Design, and Research

Cecil Howell is an artist with a practice that includes visual art, design, and landscape architecture. Her work studies the land, probing the geological, cultural, and ecological histories of place in order to understand how we are shaped by the ground beneath us and how we, in turn, shape it. After 9 years of working for landscape architecture firms, include Hargreaves, Future Green, and Margie Ruddick Landscape, Cecil created her own studio, Object + Field in order to expand her practice beyond the built environment and into artistic explorations of the human imagination.

Since opening Object + Field, she has collaborated with the renowned artist, Maya Lin and designer, Edwina von Gal. She has been awarded numerous residencies and her work was featured in several exhibitions and magazines, including Wonderground Journal (Fall 2021) and Orion (Spring 2021). Additionally, she frequently collaborates with scientists helping them visualize their research and data.

cecil@cecilhowell.com

2024.

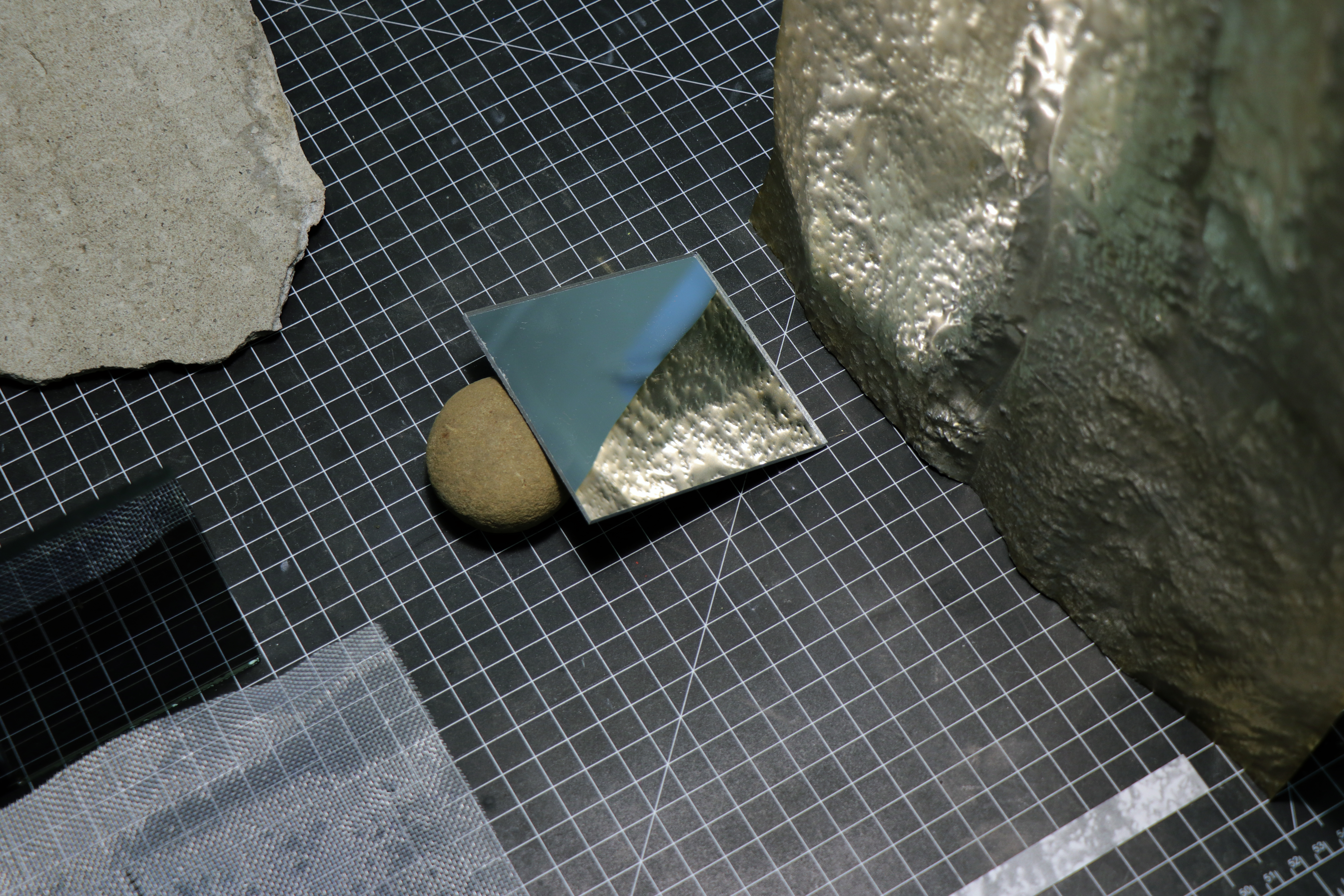

Between two mirrors

A crack in the sidewalk, a new record high temperature, a

memory of this same corner in winter, a glance at the map: as the mind flitters

between these places, scales, and thoughts, what is the experience of being in

landscape? This series, Between Two Mirrors, is centered on this question.

The installations begin with impressions of the ground; removed from their context they shed their scale and flip, multiply, obscure and deform in the mirrors, glass, and stone. The installation renders the landscape as a swirl of particulate matter: a metamorphosis of bits of images, terrain, and experiences that accumulate, however briefly, into a groundless place.

![]()

![]()

The installations begin with impressions of the ground; removed from their context they shed their scale and flip, multiply, obscure and deform in the mirrors, glass, and stone. The installation renders the landscape as a swirl of particulate matter: a metamorphosis of bits of images, terrain, and experiences that accumulate, however briefly, into a groundless place.

2024.

Phantom Limb

The scientist Lauren Oakes writes that a forest is ‘a stream of matter and energy’, a fitting description for a city as well. ‘Phantom Limb’ presses pause on this stream for a moment, arresting the flow of growth and decay long enough for us to bear witness. Rising from the ground as a grid of wooden dowels, the sculpture creates a scaffolding on which branches float. The branches, in turn, provide the cross supports necessary to strengthen the orthogonal structure of the grid. ‘Phantom Limb’ flickers between movement and suspension, hewn and raw wood, the grid and organic forms; creating a tension that energizes the sculpture.

2024.

These infinitely obscure lives

This is an archive of the ephemeral. It is a series of drawings, primarily in pastel on paper, of the ground.

Each drawing begins with a memory of the ground in mind, but moves away from a particular place/time as the composition and emotion of the drawing unfolds. In this way they are part diagram and part dream, part map and part memory. The series highlights the accumulation of subtle compositions that make our days, but also speak to the fragility I feel, we all feel, so acutely right now; with a gust of wind everything changes.